Разделы библиотеки

Леви Марк

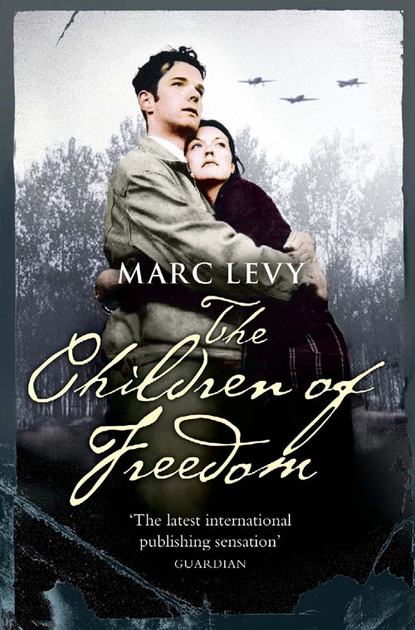

The Children of Freedom

| Предыдущая страница | Следующая страница |

1

You must understand the context within which we were living; context is important, as in the case of a sentence, for example. Once removed from its context it often changes its meaning, and during the years to come, so many sentences will be removed from their context in order to judge in a partial way and to condemn more easily. It’s a habit that won’t be lost.

In the first days of September, Hitler’s armies had invaded Poland; France had declared war and nobody here or there doubted that our troops would drive back the enemy at the borders. Then the flood of German armoured divisions had swept through Belgium, and in a few weeks a hundred thousand of our soldiers would die on the battlefields of the North and the Somme.

Marshal Pétain was appointed to head the government; two days later, a general who refused to accept defeat launched an appeal for resistance from London. Pétain chose to sign the surrender of all our hopes. We had lost the war so quickly.

By swearing allegiance to Nazi Germany, Marshal Pétain led France into one of the darkest periods of her history. The Republic was abolished in favour of what would henceforth be called the French State. The map was divided by a horizontal line and the nation separated into two zones, one in the north, which was occupied, and the other in the south, which was allegedly free. But freedom there was entirely relative. Each day saw its share of decrees published, driving back into danger two million foreign men, women and children who now lived in France without rights: the right to carry out their professions, to go to school, to move around freely and soon, very soon, the very right to exist.

The nation had become amnesiac about the foreigners who came from Poland, Romania, Hungary, these Spanish or Italian refugees, and yet it had desperate need of them. It had been vitally necessary to repopulate a France that, twenty-five years earlier, had been deprived of a million and a half men who had died in the trenches of the Great War. Almost all my friends were foreigners, and they had all experienced the repression and abuses of power already perpetrated in their country for several years. German democrats knew who Hitler was, combatants in the Spanish Civil War knew about Franco’s dictatorship, and those from Italy knew about Mussolini’s Fascism. They had been the first witnesses of all the hatred, all the intolerance, of this pandemic that was infesting Europe, with its terrible funeral cortège of deaths and misery. Everyone already knew that defeat was only a foretaste; the worst was yet to come. But who would have wanted to listen to the bearers of bad news? France now no longer needed them. So, whether they had come from the East or the South, these exiles were arrested and interned in camps.

Marshal Pétain had not only given up, he was going to collude with Europe’s dictators, and in our country, which was falling asleep around this old man, they were all already crowding around: the head of the government, ministers, prefects, judges, the police, and the Militia; each more eager than the last to carry out their terrible work.

Everything began like a children’s game, three years earlier, on 10 November 1940. The unimpressive French Marshal, surrounded by a few prefects with silver laurels, came to Toulouse to start a tour of the free zone of a country that was in fact a prisoner of his defeat.

Those directionless crowds were a strange paradox, filled with wonder as they watched the Marshal raise his baton, the sceptre of a former leader who had returned to power, bringing a new order with him. But Pétain’s new order would be an order of misery, segregation, denunciations, exclusions, murders and barbarity.

Some of those who would soon form our brigade knew about the internment camps, where the French government had locked up all those who had made the mistake of being foreigners, Jews or Communists. And in these camps in the South West, whether at Gurs, Argelès, Noé or Rivesaltes, life was abominable. Suffice to say that for anyone who had friends or family members who were prisoners, the arrival of the Marshal felt like a final assault on the small amount of freedom we had left.

Since the population was preparing to acclaim this very Marshal, we had to sound our alarm bell, awake people from this terribly dangerous fear, this fear that overcomes crowds and leads them to throw in the towel, to accept anything; to keep silent, with the sole, cowardly excuse that their neighbours are doing the same and that if their neighbours are doing the same, then that’s what they should do.

For Caussat, one of my little brother’s best friends, for Bertrand, Clouet or Delacourt, there’s no question of throwing in the towel, no question of keeping silent, and the sinister parade that is about to take place in the streets of Toulouse will be the setting for a committed declaration.

What matters today is that words of truth, a few words of courage and dignity, rain down upon the procession. A text that is clumsily written, but that nonetheless denounces what ought to be denounced; and after that, what does it matter what the text says or doesn’t say? Then we still have to work out how to make the tracts as broadly balanced as possible, without getting ourselves arrested on the spot by the forces of order.

But my friends have it all worked out. A few hours before the procession, they cross Esquirol Square with armfuls of parcels. The police are on duty, but who cares about these innocent-looking adolescents? Here they are at the right spot, a building at the corner of rue de Metz. So, all four slip into the stairwell and climb up to the roof, hoping that there won’t be any observer up there. The horizon is empty and the city stretched out at their feet.

Caussat assembles the mechanism that he and his friends have devised. At the edge of the roof, a small board lies on a small trestle, ready to tip up like a swing. On one side they lay the pile of tracts that they have typed out, on the other side a can full of water. There is a small hole in the bottom of the vessel. Look: the water is trickling out into the guttering while they are already running off towards the street.

The Marshal’s car is approaching; Caussat lifts his head and smiles. The limousine, a convertible, moves slowly up the street. On the roof, the can is almost empty and no longer weighs anything; so the plank tips up and the tracts flutter down. Today, 10 November 1940, will be the felonious Marshal’s first autumn. Look at the sky: the sheets of paper pirouette and, to the supreme delight of these street urchins with their improvised courage, a few of them land on Marshal Pétain’s peaked cap. People in the crowd bend down and pick up the leaflets. There is total confusion, the police are running about in all directions, and those who think they seek these kids cheering the procession like all the others don’t realise that it’s their own first victory that they’re celebrating.

They have dispersed and are now going their separate ways. As he goes home this evening, Caussat cannot have any idea that three days later he’ll be denounced and arrested, and will spend two years in the municipal jails of Nîmes. Delacourt doesn’t know that in a few months he will be killed by French police officers in a church in Agen, after being pursued and taking refuge there; Clouet is unaware that, next year, he will be executed by firing squad in Lyon; as for Bertrand, nobody will find the corner of a field beneath which he lies. On leaving prison, his lungs eaten away by tuberculosis, Caussat will rejoin the Maquis. Arrested once again, this time he will be deported. He was twenty-two years old when he died at Buchenwald.

You see, for our friends, everything began like a children’s game, a game played by children who will never have time to become adults.

Those are the people I must talk to you about: Marcel Langer, Jan Gerhard, Jacques Insel, Charles Michalak, José Linarez Diaz, Stefan Barsony, and all those who will join them during the ensuing months. They are the first children of freedom, the ones who founded the 35th brigade. Why? In order to resist! It’s their story that matters, not mine, and forgive me if sometimes my memory fails me, if I’m confused or get a name wrong.

What do names matter, my friend Urman said one day; there were few of us but we were all one. We lived in fear, in secrecy, we didn’t know what the next day would bring, and it is still difficult now to reopen the memory of just one of those days.

3

Believe me, I give you my word, the war was never like a film; none of my friends had the face of Robert Mitchum, and if Odette had had even the legs of Lauren Bacall, I would probably have tried to kiss her instead of hesitating like a bloody fool outside the cinema. Particularly since it was shortly before the afternoon when two Nazis killed her at the corner of rue des Acacias. Since that day, I’ve never liked acacias.

The hardest thing, and I know it’s difficult to believe, was finding the Resistance.

Since the disappearance of Caussat and his friends, my little brother and I had been brooding. At high school, between the anti-Semitic comments of the teacher of history and geography, and the sarcastic remarks of the sixth-form boys we fought with, life wasn’t much fun. I spent my evenings next to the wireless set, listening for news from London. On our return to school for the autumn term, we found small leaflets on our desks entitled ‘Combat’. I saw the boy slip out of the classroom; he was an Alsatian refugee called Bergholtz. I ran at top speed to join him in the schoolyard, to tell him that I wanted to do what he did, distribute tracts for the Resistance. He laughed at me when I said that, but nonetheless I became his second-in-command. And in the days that followed, when school was over, I waited for him on the pavement. As soon as he reached the corner of the street I started walking, and he speeded up to join me. Together, we slid Gaullist newspapers into letterboxes; sometimes we threw them from the platforms of tramcars before jumping off while they were in motion and running away.

One evening, Bergholtz didn’t appear when school ended; or the next day, either…

From then on, when school ended I and my little brother Claude would take the little train that ran along beside the Moissac road. In secret, we went to the ‘Manor’. This was a large house where around thirty children were living in hiding – children whose parents had been deported: Girl Guides and Scouts had gathered them together and were taking care of them. Claude and I went there to hoe the vegetable garden, and sometimes gave lessons in maths and French to the youngest children. I took advantage of each day I spent at the Manor, to beg Josette, the woman in charge, to give me a lead that would enable me to join the Resistance, and each time, she looked at me, raised her eyes to the heavens, and pretended not to know what I was talking about.

But one day, Josette took me to one side in her office.

‘I think I have something for you. Go and stand outside number 25, rue Bayard, at two o’clock in the afternoon. A passer-by will ask you the time. You will tell him that your watch isn’t working. If he says to you “You’re not Jeannot, are you?” It’s the right man.’

And that’s exactly how it happened…

I took my little brother and we met Jacques outside 25, rue Bayard, in Toulouse.

He entered the street wearing a grey overcoat and felt hat, with a pipe in the corner of his mouth. He threw his newspaper into the bin fixed to the lamp-post; I didn’t pick it up because that wasn’t the instruction. The instruction was to wait until he asked me the time. He stopped beside us, looked us up and down and when I answered that my watch wasn’t working, he said he was called Jacques and asked which of us two was Jeannot. I immediately took a step forward, since the name was definitely mine.

Jacques recruited the partisans himself. He trusted no one and he was right. I know it’s not very generous to say that, but you have to see it in context.

At that moment, I did not know that in a few days’ time, a partisan called Marcel Langer would be sentenced to death because of a French prosecutor who had demanded his head and obtained it. And nobody in France, whether in the free zone or not, doubted that after one of our people had brought down that prosecutor outside his home, one Sunday on his way to mass, no court of law would dare to demand the head of an arrested partisan again.

Also, I did not know that I would kill a bastard, a senior official in the Militia, a denunciator and murderer of so many young resistors. The militiaman in question never knew that his death had hung by a thread. That I was so afraid of firing that I could have wet myself over it, that I almost dropped my weapon and that if that filth hadn’t said, ‘Have mercy,’ this man who’d never had any for anyone, I wouldn’t have been angry enough to bring him down with five bullets in the belly.

We killed people. I’ve spent years saying it: you never forget the face of someone you’re about to shoot. But we never killed an innocent, not even an imbecile. I know it, and my children will know it too. That’s what matters.

At the moment, Jacques is looking at me, weighing me up, sniffing me almost like an animal, trusting his instinct, and then he plants himself in front of me: what he will say in two minutes will change the course of my life.

‘What exactly do you want?’

‘To reach London.’

‘Then I can’t do anything for you,’ says Jacques. ‘London is a long way away and I don’t have any contacts.’

I’m expecting him to turn his back on me and walk away but Jacques stays in front of me. His eyes are still on me; I try again.

‘Can you put me in contact with the Maquis? I would like to go and fight with them.’

‘That is also impossible,’ Jacques continues, re-lighting his pipe.

‘Why?’

‘Because you say you want to fight. You don’t fight in the Maquis; at best you collect packages, pass on messages, but resistance there is still passive. If you want to fight, it’s with us.’

‘Us?’

‘Are you ready to fight in the streets?’

‘What I want is to kill a Nazi before I die. I want a revolver.’

I had said that proudly. Jacques burst out laughing. I didn’t understand what was so funny about it; in fact I even thought it was rather dramatic! And that was precisely what had made Jacques laugh.

‘You’ve read too many books; we’re going to have to teach you how to use your head.’

His paternalistic question had annoyed me a little, but I wasn’t going to let him see my irritation. For months I’d been attempting to establish contact with the Resistance and now I was in the process of spoiling everything.

I search for the right words that don’t come, words that testify that I am someone on whom the partisans can rely. Jacques figures this out and smiles, and in his eyes I suddenly see something that might be a spark of affection.

‘We don’t fight to die, but for life, do you understand?’

It doesn’t sound like much, but that phrase hit me like a massive punch. Those were the first words of hope I had heard since the start of the war, since I had begun living without rights, without status, deprived of all identity in this country that yesterday was still mine. I’m missing my father, my family too. What has happened? Everything around me has melted away; my life has been stolen from me, simply because I’m a Jew and that’s enough for many people to want me dead.

My little brother is waiting behind me. He suspects that something important is afoot, so he gives a little cough as a reminder that he’s there too. Jacques lays his hand on my shoulder.

‘Come on, let’s move. One of the first things you must learn is never to stay still, that’s how you’re spotted. A lad waiting in the street, in times like this, always arouses suspicion.’

And here we are, walking along a pavement in a dark alleyway, with Claude following close on our heels.

‘I may have some work for you. This evening, you’ll go and sleep at 15, rue du Ruisseau, with old Mme Dublanc, she’ll be your landlady. You will tell her that you’re both students. She will certainly ask you what has happened to Jérôme. Answer that you’re taking his place, and he’s left to find his family in the North.’

I guessed that this was an open sesame that would give us access to a roof and, who could tell, perhaps even a heated room. So, taking my role very seriously, I asked who this Jérôme was, so that I’d be well-informed if old Mme Dublanc tried to find out more about her new tenants. Jacques immediately brought me back to a harsher reality.

‘He died the day before yesterday, two streets from here. And if the answer to my question, “Do you want to come into direct contact with the war?” is still yes, then let’s say he’s the one you’re replacing. This evening, someone will knock at your door. He will tell you he’s come on behalf of Jacques.’

With an accent like that, I knew very well that this wasn’t his real first name, but I knew too that when you entered the Resistance, your former life no longer existed, and your name disappeared with it. Jacques slipped an envelope into my hand.

‘As long as you keep paying the rent, old Mme Dublanc won’t ask any questions. Go and get yourselves photographed; there’s a kiosk at the railway station. Now clear off. We’ll have the opportunity to meet up again.’

Jacques continued on his way. At the corner of the alleyway, his lanky silhouette vanished into the mist.

‘Shall we get going?’ asked Claude.

I took my little brother to a café and we had just what we needed to warm ourselves up. Sitting at a table by the window, I watched the tramcar moving up the high street.

‘Are you sure?’ Claude asked, raising the steaming cup to his lips.

‘What about you?’

‘Me? I’m sure I’m going to die, but apart from that I don’t know.’

‘If we join the Resistance, it’s to live, not to die. Do you understand?’

‘Wherever did you dredge that up from?’

‘Jacques said it to me just now.’

‘So if Jacques says it…’

And then a long silence ensued. Two militiamen entered the café and sat down, paying us no attention. I was afraid that Claude might do something foolish, but all he did was shrug his shoulders. His stomach rumbled.

‘I’m hungry,’ he said. ‘I’m fed up with being hungry.’

I was ashamed of having a seventeen-year-old lad in front of me who didn’t have enough to eat, ashamed of my powerlessness; but that evening we might finally join the Resistance and then, I was certain, things would eventually change. Spring will return, Jacques would say one day, so, one day, I will take my little brother to a baker’s shop and buy him all the cakes in the world, which he will devour until he can eat no more, and that spring will be the most beautiful of my life.

We left the little café and, after a short stop in the railway station concourse, we went to the address Jacques had given us.

Old Mme Dublanc didn’t ask us any questions. She just said that Jérôme mustn’t care much about his things to leave like that. I handed her the money and she gave me the key to a ground-floor room that looked out onto the street.

‘It’s only for one person!’ she added.

I explained that Claude was my little brother, and that he was visiting me here for a few days. I think Mme Dublanc had a slight suspicion that we weren’t students, but as long as she was paid her rent, the lives of her tenants were nothing to do with her. The room wasn’t much to look at, with some old bedding, a water jug and a basin. Calls of nature were answered in a privy at the bottom of the garden.

We waited for the rest of the afternoon. At nightfall, someone knocked at the door. Not in the way that makes you jump; not the confident rap of the Militia when they’re coming to arrest you, just two little knocks. Claude opened the door. Emile entered, and I sensed immediately that we were going to be bound by friendship.

Emile isn’t very tall and he hates it when people say he’s short. It’s a year since he embarked on a clandestine life and everything about his attitude shows he’s become accustomed to it. Emile is calm and wears a funny kind of smile, as if nothing were important any more.

At the age of ten, he fled from Poland because his family were being persecuted. Aged barely fifteen, watching Hitler’s armies parading through Paris, Emile realised that the people who had previously wanted to take away his life in his own country had now come here to finish their dirty work. He stared with his child’s eyes and could never completely close them again. Perhaps that’s what gives him that odd smile; no, Emile’s not short, he’s stocky.

It was Emile’s concierge who saved him. It has to be said that in this sad France, there were some great landladies, the sort who looked at us differently, who wouldn’t accept the killing of decent people, just because their religion was different. Women who hadn’t forgotten that, immigrant or otherwise, a child is sacred.

Emile’s father had received the letter from police headquarters telling him he must go and buy yellow stars to sew onto coats, at chest level and clearly visible, the instructions said. At that time, Emile and his family were living in Paris, on rue Sainte-Marthe, in the tenth arrondissement. Emile’s father went to the police station on avenue Vellefaux; there were four children, so he was given four stars, plus one for him and another for his wife. Emile’s father paid for the stars and went back home, hanging his head, like an animal who’d been branded with a red-hot iron. Emile wore his star, and then the police raids started. It was no good rebelling, telling his father to tear off that piece of filth, nothing was any use. Emile’s father was a man who lived according to the law, and besides, he trusted this country, which had welcomed him in; here, you couldn’t do bad things to decent folk.

Emile had found lodgings in a little maid’s room in the attics. One day, as he was coming downstairs, his concierge had rushed up behind him.

‘Quick, go back up, they’re arresting all the Jews in the streets, the police are everywhere. They’ve gone mad. Quickly Emile, go up and hide.’

She told him to close his door and not answer to anyone; she would bring him something to eat. A few days later, Emile went out without his star. He returned to rue Sainte-Marthe, but there was no one now in his parents’ apartment; neither his father, nor his mother, nor his two little sisters, one aged six and the other fifteen, not even his brother, whom he’d begged to stay with him, not to go back to the apartment on rue Sainte-Marthe.

Emile had nobody left; all his friends had been arrested; two of them, who had taken part in a demo at porte Saint-Martin, had managed to escape via rue de Lancry when some German soldiers on motorcycles had machine-gunned the procession; but they had been caught. They ended up being stood up against a wall and shot. As a reprisal, a resistor known by the name of Fabien had killed an enemy officer the following day, on the metro platform at Barbès station, but that hadn’t succeeded in bringing back Emile’s two friends.

No, Emile had nobody left, apart from André, one final friend with whom he had taken a few accountancy lessons. So he went to see him, to try and get a little help. It was André’s mother who opened the door to him. And when Emile told her that his family had been taken away, that he was all alone, she took her son’s birth certificate and gave it to Emile, advising him to leave Paris as quickly as possible. ‘Do whatever you can with it; you might even get yourself an identity card.’ The name of André’s family was Berté, and they weren’t Jewish, so the certificate was a golden safe-conduct pass.

At the Gare d’Austerlitz, Emile waited as the train for Toulouse was assembled at the platform. He had an uncle down there. Then he got into a carriage, hid under a seat and didn’t move. In the compartment, the passengers had no idea that behind their feet a kid was hiding; a kid who was in fear for his life.

The train set off, but Emile stayed hidden, motionless, for hours. When the train crossed into the free zone, Emile left his hiding place. The passengers’ expressions were a sight to see when this kid emerged from nowhere; he admitted that he had no papers; a man told him to go back into his hiding place immediately, as he was accustomed to this journey and the gendarmes would soon be carrying out another check. He would let him know when he could come out.

You see, in this sad France, there were not only some great concierges and landladies, but also generous mothers, splendid travellers, anonymous people who resisted in their own way, anonymous people who refused to do as their neighbours did, anonymous people who broke the rules because they were shameful.

Into this room, which Mme Dublanc has been renting to me for a few hours, comes Emile, with his whole story, his whole past. And even if I don’t know Emile’s story yet, I can tell from the look in his eyes that we’re going to get on well.

‘So, you’re the new one are you?’ he asks.

‘We both are,’ cuts in my little brother, who hates it when people act as if he isn’t there.

‘Have you got the photos?’ asks Emile.

And he takes from his pocket two identity cards, some ration books and a rubber stamp. Once the papers have been sorted out, he stands up, turns the chair around and sits down again, astride it.

‘Let’s talk about your first mission, Jeannot. Well, as there are two of you, let’s call it the first mission for both of you.’

My brother’s eyes are sparkling. I don’t know if it’s hunger that’s gnawing away at his stomach or the new appetite for a promise of action, but I can see clearly that his eyes are sparkling.

‘You’re going to have to steal some bicycles,’ says Emile.

Claude goes back to the bed, looking downcast.

‘Is that what resisting means? Pinching bicycles? I’ve come all this way for someone to ask me to be a thief?’

‘So, do you think you’re going to carry out your missions in a car? The bicycle is the partisan’s best friend. Think for a moment, if that’s not too much to ask of you. Nobody takes any notice of a man on a bike; you’re just some guy who’s coming back from the factory or leaving for work, depending on the time. A cyclist melts into the crowd, he’s mobile, he can sneak around everywhere. You do your job, you clear off on your bike, and while people are still wondering what exactly happened, you’re already on the other side of town. So if you want to be entrusted with important missions, start by going and pinching your bicycles!’

So, that was the lesson for the day. We still had to work out where we were going to pinch the bikes from. Emile must have anticipated my question. He had already done some research and told us about the corridor of an apartment building where three bicycles slept, never chained up. We’d have to act fast; if all went well, we were to come and find him early in the evening at the house of a friend. He asked me to learn the friend’s address by heart. It was a few kilometres away, in the outskirts of Toulouse; a small, disused railway station in the Loubers district. ‘Hurry,’ Emile had insisted, ‘you must be there before the curfew.’ It was spring, darkness would not fall for several hours, and the apartment building with the bikes wasn’t far from here. Emile left and my little brother continued to sulk.

I managed to convince Claude that Emile wasn’t wrong and also that it was probably a test. My little brother moaned, but agreed to follow me.

We made a remarkable success of our first mission. Claude was hiding in the street; after all, you could get two years in prison for stealing a bicycle. The corridor was deserted and, as Emile had promised, there were indeed three bikes there, resting against each other, and none of them chained up.

Emile told me to nab the first two, but the third one, the one against the wall, was a sports model with a flaming red frame and handlebars with leather grips. I moved the one in front, which fell with a horrifying racket. Already I could see myself having to gag the concierge, but by a stroke of good luck the lodge was empty and nobody disturbed my work. The bike I fancied wasn’t easy to capture. When you’re afraid, your hands become clumsier. The pedals were caught up and whatever I did, I couldn’t separate the two bicycles. After a thousand attempts, all the while trying to calm my pounding heart as best I could, I finally succeeded. My little brother peeped in, finding that time dragged when you were hanging about on the pavement, all alone.

-Good grief, what on earth are you up to?

-Here, take your bike and stop moaning.

-Why can’t I have the red one?

-Because it’s too big for you!

Claude started moaning again, and I pointed out to him that we were on an official mission and that this was not the time for an argument. He shrugged his shoulders and mounted his bicycle. A quarter of an hour later, pedalling flat out, we were following the route of the disused railway line in the direction of the small former railway station at Loubers.

Emile opened the door to us.

‘Look at these bikes, Emile!’

Emile assumed a strange expression, as if he wasn’t pleased to see us, and then he let us in. Jan, a tall, thin guy, looked at us and smiled. Jacques was in the room too; he congratulated us both and, seeing the red bike I’d chosen, he burst out laughing again.

‘Charles will disguise them so they’re unrecognisable,’ he added, laughing even louder.

I still didn’t see what was funny about it and apparently neither did Emile, in view of the expression he was wearing.

A man in a vest came down the stairs. He was the one who lived here in this little disused station, and for the first time I met the brigade’s handyman. The one who took apart and reassembled the bikes, the one who made the bombs to blow up the locomotives, the one who explained how, on railway flat wagons, you could sabotage the cockpits assembled in the region’s factories, or how to cut the cables on the wings of bombers, so that once they were assembled in Germany, Hitler’s planes wouldn’t take off for quite a while. I must tell you about Charles, this friend who had lost all his front teeth in the Spanish Civil War, this friend who had passed through so many countries that he had mixed up the languages and invented his own dialect, to the point where nobody could really understand him. I must tell you about Charles because, without him, we would never have been able to accomplish all that we were going to do in the coming months.

That evening, in that ground-floor room in an old, disused railway station, we’re all aged between seventeen and twenty, we’re soon going to make war and despite his hearty laugh just now when he saw my red bike, Jacques looks worried. I’m soon going to find out why.

Someone knocks at the door, and this time Catherine comes in. She’s beautiful, is Catherine, and what’s more, from the look she exchanges with Jan, I’d swear they’re a couple, but that’s impossible. Rule number one: no love affairs when you’re living a secret life in the Resistance, Jan will explain while we’re sitting at the table, as he introduces us to the way we must behave. It’s too dangerous; if you’re arrested, there’s a risk that you’ll talk to save the one you love. ‘A condition of being a partisan is that you don’t get yourself attached,’ Jan said. And yet he feels an attachment to each one of us and I can work that out already. My little brother isn’t listening to anything, he’s devouring Charles’s omelette; at times, I tell myself that if I don’t stop him, he’ll end up eating the fork as well. I can see him eyeing up the frying pan. Charles sees him too, and smiles. He gets up and goes to serve him up another portion. It’s true that Charles’s omelette is delicious, even more so for our bellies, which have been empty for so long. Behind the station, Charles cultivates a kitchen garden. He has three hens and even some rabbits. He’s a gardener, is Charles, anyway that’s his cover and the people around here like him a lot, even if his accent makes it clear that French isn’t his native tongue. He gives them lettuces. And besides, his kitchen garden is a splash of colour in the dreary area, so the people around here like him, this improvised colourist, even if he does have a terrible foreign accent.

Jan speaks in a steady voice. He is hardly any older than I am but he already has the air of a mature man and his calm commands respect. What he tells us thrills us, there is a sort of aura around him. What Jan says is terrible: he talks to us about the missions carried out by Marcel Langer and the first members of the brigade. They’ve already been operating in the Toulouse area for a year, Marcel, Jan, Charles and José Linarez. Twelve months, in the course of which they’ve thrown grenades at a dinner party for Nazi officers, blown up a barge filled to bursting with petrol, burned down a garage for German lorries. So many operations that the list alone is too long to tell in a single evening; Jan’s words are terrible, and yet he exudes a sort of tenderness that everyone here misses, abandoned children that we are.

Jan’s stopped talking. Catherine is back from town with news of Marcel, the leader of the brigade. He’s incarcerated in Saint-Michel prison.

His downfall was so stupid. He went to Saint-Agne station to collect a suitcase conveyed by a young woman in the brigade. The suitcase contained explosives, sticks of dynamite, of ablonite EG antifreeze, twenty-four millimetres in diameter. These sixty gramme sticks were put aside by a few Spanish miners who were sympa-thisers, and who were employed in the factory at the Paulilles quarry.

It was José Linarez who had organised the mission to collect the suitcase. He had refused to let Marcel get on board the little train that shuttled between the Pyrenean towns; the girl and a male Spanish friend had made the return trip alone as far as Luchon and taken possession of the package; the handover was to take place at Saint-Agne. The halt at Saint-Agne was more of a level crossing than a railway station proper. There weren’t many people in this undeveloped corner of the countryside; Marcel waited behind the barrier. Two gendarmes were patrolling, looking out for any travellers transporting foodstuffs destined for the region’s black market. When the girl got off, her eyes met those of a gendarme. Feeling she was being watched, she took a step back, immediately arousing the man’s interest. Marcel instantly realised that she was going to be stopped, so he stepped in front of her. He signalled to her to approach the gate that separated the halt from the track, took the suitcase from her hands and ordered her to get the hell out of it. The gendarme didn’t miss any of this and rushed at Marcel. When he asked him what the suitcase contained, Marcel replied that he didn’t have the key. The gendarme wanted him to follow him, so Marcel told him that it was a consignment for the Resistance and that he must let him pass.

The gendarme didn’t care about his story, and Marcel was taken to the central police station. The typed report stated that a terrorist in possession of sixty sticks of dynamite had been arrested at Saint-Agne station.

The affair was an important one. A police superintendent answering to the name of Caussié took over, and for days Marcel was beaten. He didn’t let slip a single name or address. The conscientious superintendent went to Lyon to consult his superiors. At last the French police and the Gestapo had a case that they could use as an example: a foreigner in possession of explosives, and what’s more he was a Jew and a Communist too; in other words a perfect terrorist and an eloquent example that they were going to use to stem any desire for resistance in the population.

Once charged, Marcel was handed over to the special section of the public prosecutor’s department. Deputy Public Prosecutor Lespinasse, a man of the extreme right who was fiercely anti-Communist and dedicated to the Vichy regime, would be the ideal prosecutor; the Marshal’s government could count on his fidelity. With him, the law would be applied without any restraint, without any attenuating circumstances, without any concern for the context. Scarcely had Lespinasse been given the task when, swollen with pride, he swore before the court to obtain Marcel’s head.

In the meantime, the young woman who had escaped arrest had gone to warn the brigade. The friends immediately got into contact with Maître Arnal, one of the best lawyers at the court. For him the enemy was German, and the moment had come to take up position in favour of these people who were being persecuted without reason. The brigade had lost Marcel, but it had just won over to its cause a man of influence, who was respected in the town. When Catherine talked to him about his fees, Arnal refused to be paid.

The morning of 11 June 1943 will be terrible, terrible in the memory of partisans. Everyone’s leading their own lives and soon destinies will intersect. Marcel is in his cell. He looks out through the skylight at the dawn; today is the day of his trial. He knows he’s going to be convicted, he has little hope. In an apartment not far from there, the old lawyer who is in charge of his defence is putting his notes in order. His domestic help comes into his office and asks him if he wants her to make him some breakfast. But Maître Arnal isn’t hungry on this morning of 11 June 1943. All night he has heard the voice of the deputy prosecutor demanding his client’s head; all night he has tossed and turned in his bed, searching for strong words, the right words that will counter the indictment of his adversary, prosecuting counsel Lespinasse.

And while Maître Arnal revises again and again, the fearsome Lespinasse enters the dining room of his opulent house. He sits down at the table, opens his newspaper and drinks his morning coffee, which is served to him by his wife, in the dining room of his opulent house.

In his cell, Marcel is also drinking the hot brew brought to him by the warder. An usher has just delivered him his citation to appear before the special Session of the Toulouse Court. Marcel looks out through the skylight. He thinks about his little girl, his wife, down there somewhere in Spain, on the other side of the mountains.

Lespinasse’s wife stands up and kisses her husband on the cheek. She leaves for a meeting about good works. The deputy prosecutor puts on his overcoat and looks at himself in the mirror, proud of his fine appearance, convinced that he will win. He knows his text by heart, a strange paradox for a man who really doesn’t have one – a heart, that is. A black Citroën waits outside his house and is already driving him to the courthouse.

On the other side of town, a gendarme chooses his best shirt from his wardrobe. It is white, and the collar has been starched. He is the one who arrested the accused and today he has been summoned to appear. As he ties his tie, young gendarme Cabannac has moist hands. There is something not right about what is going to happen, something rotten, and Cabannac knows it; what’s more, if it happened again he would let him get away, that guy with the black suitcase. The enemies are the Boche, not lads like him. But he thinks of the French State and its administrative mechanism. He is a mere cog and he can’t be found wanting. He knows the mechanism well, does Gendarme Cabannac; his father taught him all about it, and the morality that goes with it. At the weekend, he enjoys repairing his motorbike in his father’s shed. He knows full well that if one piece happens to be missing, the whole mechanism seizes up. So, with moist hands, Cabannac tightens the knot of his tie on the starched collar of his fine white shirt and heads for the tram stop.

A black Citroën moves away into the distance and overtakes the tram. At the back of the carriage, sitting on the wooden bench, an old man rereads his notes. Maître Arnal looks up and then plunges back into his reading. The game promises to be a hard one but nothing is lost. It is unthinkable that a French court could sentence a patriot to death. Langer is a brave man, one of those who act because they are valiant. He knew that as soon as he met him in his cell. His face was so misshapen; under his cheekbones, you could make out the marks of the punches that had landed there, and the gashed lips were blue and swollen. He wonders what Marcel looked like before he was beaten up like that, before his face was punched out of shape, taking on the imprint of the violence it had suffered. They are fighting for our freedom, mused Arnal; it really isn’t complicated to work that out. If the court can’t see it yet, he’ll do his damnedest to open their eyes. Say they sentence him to prison for example, OK, that will save appearances, but death? No. That would be a judgment unworthy of French magistrates. By the time the tram halts with a screech of metal at the courthouse station, Maître Arnal has recovered the confidence necessary to plead his case well. He’s going to win this case, he’ll cross swords with his adversary, Deputy Prosecutor Lespinasse and he will save that young man’s head. Marcel Langer, he repeats to himself softly as he climbs the steps.

While Maître Arnal walks down the Palais’ long corridor, Marcel, handcuffed to a gendarme, waits in a small office.

The trial takes place in camera. Marcel is in the dock, Lespinasse stands up and doesn’t even glance at him; he scorns the man he wants to convict, and the last thing he wants is to get to know him. A few scant notes lie in front of him. First, he pays homage to the gendarmerie’s perspicacity, which ensured that a dangerous terrorist was prevented from doing harm, and then he reminds the court of its duty, that of observing the law and seeing that it is respected. Pointing at the man on trial without once looking at him, Deputy Prosecutor Lespinasse voices his accusations. He enumerates the long list of murder attempts the Germans have suffered, and he recalls also that France signed the armistice in honour and that the accused, who is not even French, has no right to call the State’s authority into question again. To grant him extenuating circumstances would be tantamount to scorning the Marshal’s word. ‘The reason the Marshal signed the armistice was for the good of the Nation,’ Lespinasse continues, with vehemence. ‘And a foreign terrorist has no right to judge to the contrary.’

Finally, to add a little humour, he reminds the court that Marcel Langer was not carrying firecrackers for the fourteenth of July, but explosives destined to destroy German installations, and so disturb the citizens’ tran-quillity. Marcel smiles. The fireworks of the fourteenth of July are a long way away.

Should the defence put forward arguments of a patriotic nature, with the aim of granting Langer extenuating circumstances, Lespinasse again reminds the court that the defendant is a stateless person, that he chose to abandon his wife and little girl in Spain, where he had previously gone to fight, although he was Polish and a stranger to the conflict. That France, in its indulgence, had welcomed him in, but not to come here, to our homeland, bringing disorder and chaos. ‘How can a man without a homeland claim to have acted according to a patriotic ideal?’ And Lespinasse sniggers at his own witticism, his turn of phrase. Fearing that the court may be afflicted with amnesia, he reminds them of the act of accusation, lists the laws that sentence such acts to capital punishment, and congratulates himself on the severity of the laws in force. Then he pauses for a moment, turns towards the man he is accusing and finally consents to look at him. ‘You are a foreigner, a Communist and a partisan, three separate reasons, each of which is sufficient for me to ask the court for your head.’ This time, he turns away towards the magistrates and in a calm voice demands that Marcel Langer should be sentenced to death.

Maître Arnal is white-faced. He stands up at the same moment as the smug Lespinasse sits down. The old lawyer’s eyes are half-closed, his chin tilted forward, his hands clenched in front of his mouth. The court is motionless, silent; the clerk barely dares lay down his pen. Even the gendarmes are holding their breath, waiting for him to speak. But for the moment, Maître Arnal cannot say anything, overcome as he is with nausea.

He is therefore the last person here to realise that the rules have been rigged, that the decision has already been taken. And yet, in his cell, Langer had told him he knew that he was condemned in advance. But the old lawyer still believed in justice and had kept on assuring him that he was wrong, that he would defend him as he should and that the judgment would be in his favour. Behind him, Maître Arnal feels Marcel’s presence, thinks he can hear him murmuring: ‘You see, I was right, but I don’t blame you, in any case, you couldn’t do anything.’

So he raises his arms, his sleeves seeming to float in the air, breathes in and launches into a final speech for the defence. How can the gendarmerie’s work be praised, when the defendant’s face bears the stigmata of the violence he has suffered? How can anyone dare to joke about the fourteenth of July in this France that no longer has the right to celebrate it? And what does the prosecutor really know about these foreigners whom he accuses?

As he got to know Langer in the visiting room, he was able to find out how much these stateless individuals, as Lespinasse calls them, love this country that has welcomed them in even to the point where, like Marcel Langer, they will sacrifice their lives to defend it. The accused is not the man the prosecutor depicts. He is a sincere and honest man, a father who loves his wife and his daughter. He did not leave Spain to join the fighting, but because, more than all, he loves humanity and human freedom. Yesterday, wasn’t France still the land of human right? Sentencing Marcel Langer to death means sentencing the hope for a better world.

Arnal’s plea lasted more than an hour, using up his last reserves of strength; but his voice rings out without an echo in this court that has already given its verdict. Today, 11 June 1943, is a sad day. The sentence has been pronounced, and Marcel will be sent to the guillotine. When Catherine hears the news in Arnal’s office, her lips purse tightly and she takes the blow. The lawyer swears that he has not finished, that he will go to Vichy to plead for clemency.

That evening, in the little disused railway station that serves Charles as lodgings and a workshop, the table has grown. Since Marcel’s arrest, Jan has taken command of the brigade. Catherine sat down next to him. From the look they exchanged, I knew this time that they loved each other. And yet the look in Catherine’s eyes is sad, and her lips can barely utter the words she has to tell us. She is the one who announces to us that Marcel has been sentenced to death by a French prosecutor. I don’t know Marcel, but like all the comrades around the table, I have a heavy heart and as for my little brother, he has completely lost his appetite.

Jan paces up and down. Everyone is silent, waiting for him to speak.

‘If they carry it out, we shall have to kill Lespinasse, to scare the hell out of them; otherwise, these scum will sentence to death all the partisans who fall into their hands.’

‘While Arnal is lodging his plea for clemency, we can prepare for the operation,’ continues Jacques.

‘It will take a lot more time,’ mutters Charles in his strange language.

‘And in the meantime, aren’t we going to do anything?’ cuts in Catherine, who is the only one who’s understood what he was saying.

Jan thinks and continues to pace up and down the room.

‘We must act now. Since they have condemned Marcel to death, let’s condemn one of their people too. Tomorrow, we’ll take down a German officer right in the middle of the street and we’ll distribute a tract to explain why we did it.’

I certainly don’t have much experience of political operations, but an idea is going around in my head and I venture to speak.

‘If we really want to scare the hell out of them, it would be even better to drop the tracts first, and take down the German officer afterwards.’

‘And that way they’ll all be on their guard. Have you got any more ideas like that?’ argues Emile, who seems decidedly mad at me.

‘My idea’s not bad, not if the operations are a few minutes apart and carried out in good order. Let me explain. If we kill the Boche first and drop the tracts afterwards, we’ll look like cowards. In the eyes of the population, Marcel was judged first and only then sentenced.

‘I doubt that La Dépêche will report on the arbitrary condemnation of a heroic partisan. They’ll announce that a terrorist has been sentenced by a court. So let’s play by their rules; the town must be with us, not against us.’

Emile wanted to shut me up, but Jan signalled to him to let me speak. My reasoning was logical, I just needed to find the right words to explain to my friends what I had in mind.

‘First thing tomorrow morning, we should print a communiqué announcing that as a reprisal for Marcel Langer’s death penalty, the Resistance has condemned a German officer to death. We should also announce that the sentence will be applied that very afternoon. I will take care of the officer, and – at the same moment – you will drop the tract everywhere. People will become aware of it immediately, while news of the operation will take a lot of time to spread through the town. The newspapers won’t talk about it until tomorrow’s edition, and the right chronology of events will appear to have been respected.’

One by one, Jan consults the members seated at the table, and eventually his eyes meet mine. I know that he agrees with my reasoning, except perhaps for one detail: he raised an eyebrow slightly at the moment when I mentioned in passing that I would kill the German myself.

In any event, if he hesitates too much, I have an irrefutable argument; after all, the idea is mine, and besides, I stole my bicycle, so I’ve complied with the rules of the brigade.

Jan looks at Emile, Alonso, Robert and then Catherine, who agrees with a nod. Charles has missed none of the scene. He stands up, heads for the cupboard under the stairs and comes back with a shoe box. He hands me a barrel revolver.

‘Be better if you and brother here sleep tonight.’

Jan approaches me.

‘Right, you’ll fire the gun; Spaniard,’ he said, designating Alonso, ‘you will be the lookout; and you, young one, you’ll hold the bicycle in the direction of the getaway.’

There. Of course, said like that it’s quite anodyne, except that Jan and Catherine went away again into the night, and I now had a pistol in my hand, with six bullets, and my cretin of a little brother who wanted to know how it worked. Alonso leant over towards me and asked me how Jan knew that he was Spanish, when he hadn’t said a word all evening. ‘And how did he know that the shooter would be me?’ I told him with a shrug of my shoulders. I hadn’t answered him, but my friend’s silence testified that my question must have gained the upper hand over his.

That night, we slept for the first time in Charles’s dining room. I lay down completely knackered, but never-theless with a massive weight on my chest; first my little brother’s head – he’d acquired the bloody awful habit of sleeping pressed up against me since we were separated from our parents – and, worse still, the pistol in the left pocket of my jacket. Even though there weren’t any bullets in it, I was afraid that in my sleep, it might blow a hole in my little brother’s head.

As soon as everyone was properly asleep, I got up on my tiptoes and went out into the garden behind the house. Charles had a dog, which was as gentle as it was stupid.

I’m thinking of it because that night, I had a desperate need for its spaniel muzzle. I sat down on the chair under the washing line, I looked at the sky and I took the gun out of my pocket. The dog came to sniff at the barrel, and I stroked its head, telling it that it would definitely be the only one in my lifetime allowed to sniff the barrel of my weapon. I said that because at that moment I really needed to put on a bold front.

One late afternoon, by stealing two bikes, I had entered the Resistance, and it’s only now, hearing my little brother, snoring like a child with a blocked nose, that I really realised it. Jeannot, Marcel Langer brigade; during the months to come, I was going to blow up trains, electricity pylons, sabotage engines and the wings of aircraft.

I belonged to a band of partisans that was the only one to have succeeded in bringing down German bombers…on bicycles.

Получить полную версию книги можно по ссылке - Здесь

| Предыдущая страница | Следующая страница |

|