Разделы библиотеки

Guillou Jan

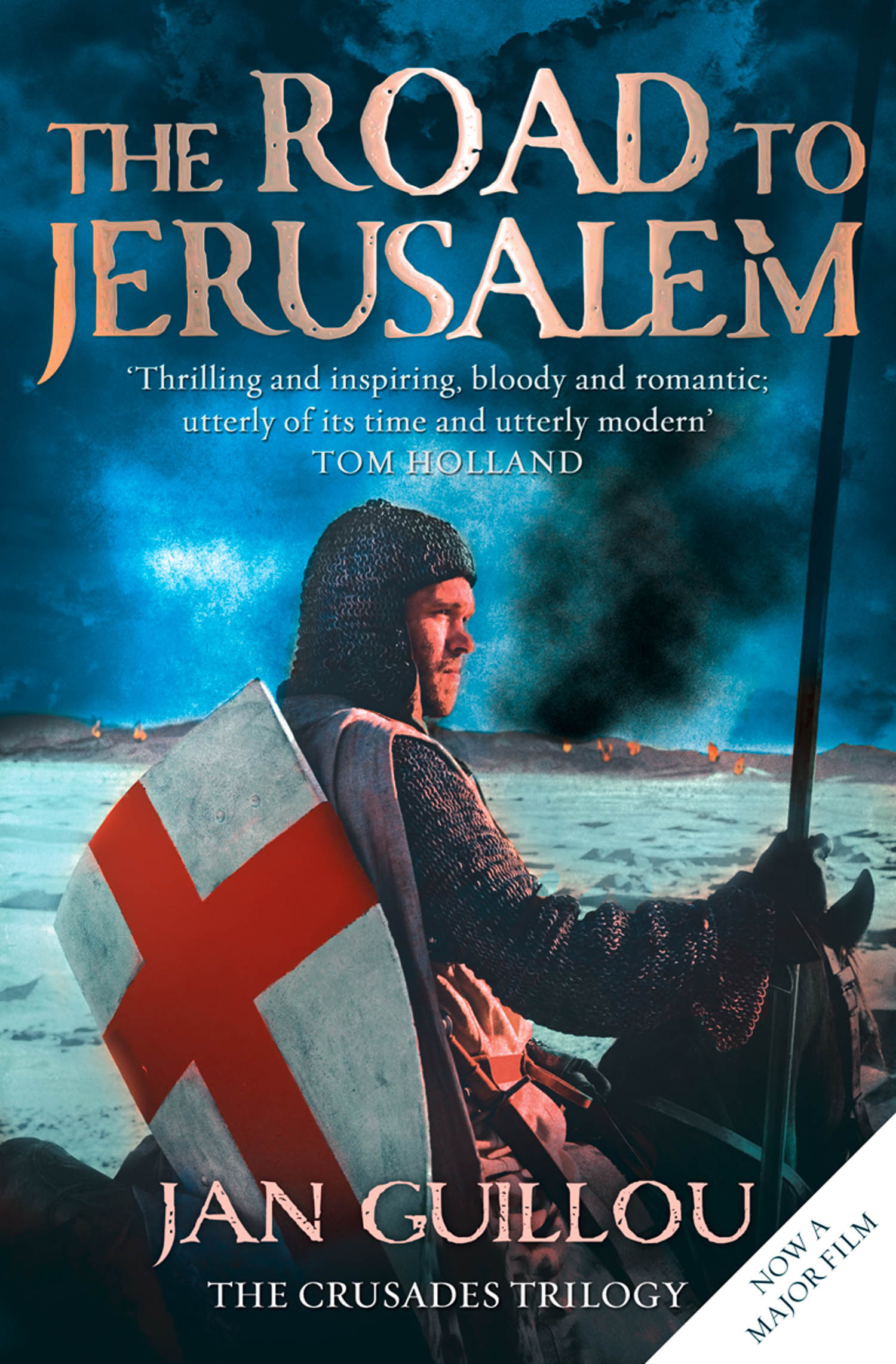

The Road to Jerusalem

Аннотация к произведению The Road to Jerusalem - Ян Гийу

| Следующая страница |

Copyright

JAN GUILLOU

The Crusades Trilogy

The Road

to Jerusalem

Translated by Steven T. Murray

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

Copyright © Jan Guillou

Jan Guillou asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Translation copyright © Steven T. Murray 2009 First published in Swedish as Vägen till Jerusalem

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Source ISBN: 9780007285853

Ebook edition © FEBRUARY 2009 ISBN: 9780007313952

Version 2019-02-22

Dedication

‘The road to hell is paved with good intentions’

Jacula Prudentum, 1651, no. 170

Contents

Title Page Copyright Dedication Principal Characters Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Keep Reading About the Author About the Publisher

PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS

THE FOLKUNG CLAN

(including the Bjälbo branch)

Magnus Folkesson, master of Arnäs

Fru Sigrid, first wife of Magnus Folkesson and mother of Eskil and Arn

Erika Joarsdotter, second wife of Magnus Folkesson

Eskil Magnusson, first son of Magnus Folkesson

Arn Magnusson, second son of Magnus Folkesson

Birger Brosa, younger brother of Magnus Folkesson

THE ERIK CLAN

King Erik Jedvardsson, king of Svealand

Joar Jedvardsson, brother of Erik Jedvardsson

Kristina Jedvardsson, wife of Erik Jedvardsson (and kinswoman to Fru Sigrid)

King Knut Eriksson, son of Erik Jedvardsson

THE SVERKER CLAN

King Sverker, king of Eastern Götaland

Queen Ulvhild, first wife of King Sverker

King Karl Sverkersson, son of King Sverker and Ulvhild

Rikissa, second wife of King Sverker

Knut Magnusson, son from Rikissa’s first marriage, later king of Denmark

Emund Ulvbane (aka ‘Emund One-Hand’)

Boleslav and Kol, half-brothers of King Karl Sverkersson

THE PÅL CLAN

Algot Pålsson, steward of Husaby

Katarina Algotsdotter, older daughter of Algot

Cecilia Algotsdotter, younger daughter of Algot

THE CLERGY (Cistercians from France)

Father Henri de Clairvaux, prior of Varnhem

Brother Guilbert de Beaune, the weapons smith

Brother Lucien de Clairvaux, the gardener

Brother Guy le Breton, the fisherman

Brother Ludwig de Bêtecourt, the music master

Brother Rugiero de Nîmes, the chef

Archbishop Stéphan

THE DANES

King Sven Grate of Denmark

Magnus Henriksen, the king-slayer

THE ROAD TO JERUSALEM

In the year of Grace 1150, when the ungodly Saracens, the scum of the earth and the vanguard of the Antichrist, inflicted many defeats on our forces in the Holy Land, the Holy Spirit descended upon Fru Sigrid of Arnäs and gave her a vision which changed her life.

Perhaps it could also be said that this vision had the effect of shortening her life. What is certain is that she was never the same again. Less certain is what the monk Thibaud wrote much later, that at the very moment the Holy Spirit revealed itself to Sigrid, a new realm was actually created up in the North, which at the end of the era would come to be known as Sweden.

It was at the Feast of St Tiburtius, the day regarded as the first day of summer, when the ice melts in Western Götaland. Never before had so many people gathered in Skara, since it was no ordinary mass that was now to be celebrated. The new cathedral was going to be consecrated.

The ceremonies were already into their second hour. The procession had made its three circuits around the church, moving with infinite slowness because Bishop Ödgrim was a very old man, shuffling along as if it were his last journey. He also seemed a bit confused, because he had read the first prayer inside the blessed church in the vernacular instead of in Latin:

God, Thou who invisibly preserveth everything

but maketh Thy power visible for the salvation of

humanity,

take Thy house and rule in this temple,

so that all who gather here to pray

might share in Thy solace and aid.

And God did indeed make His power visible, though whether for the salvation of humanity or for other reasons is unknown. It was a pageant like none ever seen before in all of Western Götaland: there were dazzling colours from the vestments of the bishops in light-blue and dark-red silk with gold thread; there were overpowering fragrances from the censers which the canons swung as they walked about, and there was a music so heavenly that no ear in Western Götaland could ever have heard its like before. And if you raised your eyes it was like looking up into Heaven itself, but under a roof. It was inconceivable that even the Burgundian and English stonemasons could have created such a high vault that would not come crashing down, if for no other reason than that God might be angry at the vanity of attempting to build an edifice that could reach up to Him.

Fru Sigrid was a practical woman. Because of this some people said that she was a hard woman. She had absolutely not wanted to set off on the difficult journey to Skara, since spring had come early and the roads had softened to a sea of mud. She was uneasy at the thought of sitting in a wagon that jolted and bounced and careened back and forth, in her blessed condition. More than anything else in this earthly life, she feared the coming birth of her second child. And she knew very well that if a cathedral was being consecrated, it would mean standing on the hard stone floor for several hours and falling to her knees repeatedly in prayer. She was well versed in the many rules of church life, surely far better than most of the noblemen and their daughters surrounding her just now, but she had not acquired this knowledge through faith or free will. When she was sixteen years old her father, with good reason, took it into his head that she was paying too much attention to a kinsman from Norway of far too low birth, which might have led to something that belonged only within the sacrament of marriage, as her father gruffly summed up the problem. So she had been sent away for five years to a convent in Norway. She probably never would have been released if she hadn’t come into an inheritance from a childless uncle in Eastern Götaland; thus she became a woman to be married off instead of languishing in a convent.

So she knew when to stand and when to kneel, when to rattle off the Pater Nosters and Ave Marias which some of the bishops at the altar were intoning, and when to say her own prayers. Each time she had to say her own prayer, she prayed for her life.

God had given her a son three years before. It had taken two days and nights to give birth to him; twice the sun had gone up and gone down again while she was bathed in sweat, anguish, and pain. She knew she was going to die, and in the end all the good women helping her knew it too. They had sent for the priest in Forshem, and he had given her extreme unction and forgiveness for her sins.

Never again, she had hoped. Never again such pain, such terror of death, she now prayed. It was a selfish thing to ask, she knew that. It was common for women to die in childbed, and a human being is born in pain. But she had made the mistake of praying to the Holy Virgin to spare her, and she had tried to fulfil her marital duties in such a way that they would not lead to another childbed. Their son, Eskil, had lived after all.

The Holy Virgin had punished her, of course. New torments now awaited her, that was certain. And yet she prayed over and over to come through it easily.

To lighten the lesser but irksome nuisance of standing and kneeling, standing up and then kneeling down again, for hours on end, she’d had her thrall woman Sot baptized so that she could come along into God’s house. She had Sot stand next to her, and she leaned on the thrall when she had to get up and down. Sot’s big black eyes were open wide like terrified horse’s eyes, staring at everything she now observed. If she wasn’t a real Christian before then she ought to have become one by now.

Three man-lengths in front of Sigrid stood King Sverker and Queen Ulvhild. The two of them, both weighed down by age, were having more and more trouble standing up and kneeling down without too much puffing. Yet it was for their sake and not for God’s that Sigrid was in the cathedral. King Sverker held neither her Norwegian and Western Götaland kinsmen nor her husband’s Norwegian and Folkung lineage in high esteem. But now, at his advanced age, the king had grown both suspicious and anxious about his life after this earthly one. Missing the king’s great and blessed church dedication might have caused a misunderstanding. If a man or woman offended God in some way, that matter might be taken up with God Himself. Sigrid considered it worse to be on the wrong side of the king.

But during the third hour Sigrid’s head began to swim, and she was having more and more trouble kneeling down and getting up again. The child inside her kicked and stirred all the more, as if in protest. She had the feeling that the pale-yellow, polished marble floor was undulating beneath her. She thought she saw it begin to crack, as if it might suddenly open up and swallow her whole. Then she did something quite outrageous. She walked resolutely, silk skirts rustling, over to a little empty bench off to the side and sat down. Everyone saw it, the king too.

Just as she sank with relief onto the stone bench next to the church wall in the middle of the side aisle, the monks from the island of Lurö came filing in. Sigrid wiped her brow and face with a small linen handkerchief and gave her son, standing next to Sot, an encouraging wave.

Then the monks began to sing. Silently and with bowed heads they walked up the entire length of the centre aisle and took their places by the altar, where the bishops and their acolytes now drew aside. At first it sounded like a muffled, soft murmur, but then the high voices of the boys joined in. Some of the Lurö monks had brown cowls, not white, and were quite clearly young boys. Their voices rose like ethereal birds up to the huge vaults of the ceiling. When their singing had risen so high that it filled the entire enormous space, the low voices of the monks themselves joined in, singing the same melody and yet not the same. Sigrid had heard psalms sung in both two and three voices, but this had at least eight different parts. It was like a miracle, something that could not happen, since even a three-part psalm was difficult to master.

Exhausted, Sigrid stared wide-eyed in the direction of the miracle, listening with her entire being, her entire body. She began to tremble with excitement. Blackness fell over her eyes, and she no longer saw but only heard, as if her eyes too had to lend their powers to her hearing. She seemed to vanish, as if she were transmuted into tones, into a part of the holy music, more beautiful than any music ever heard in this earthly life.

A while later she came to her senses, when someone took her by the hand, and when she looked up she discovered King Sverker himself.

He patted her gently on the hand and thanked her with a wry smile because he, as an old man, was in need of a woman with child who would be the first to sit down. If a blessed woman could do so, then so too could the king, he said. It would not have looked proper for him to go first.

Sigrid firmly suppressed the idea of telling him that the Holy Spirit had just spoken to her. It seemed to her that such an admission would merely seem as if she were boasting, and kings saw more than enough of that, at least until someone chopped off their heads. Instead she quickly whispered an idea that had come to her.

As the king no doubt already knew, there was a dispute over her inheritance of Varnhem. Her kinswoman Kristina, who had recently married that upstart Erik Jedvardsson, was laying claim to half the property. But the monks on the island of Lurö needed to live in a region with less severe winters. Much of their farming had been in vain out there, and everyone knew it; not to disparage King Sverker’s great generosity in donating Lurö to them. But if she, Sigrid, now donated Varnhem to the Cistercian monks, the king could bless the gift and declare it legal, and the whole problem would be resolved. Everyone would gain.

She had been speaking quickly, in a low voice, and a little breathlessly, her heart still pounding after what she had witnessed in the heavenly music after the darkness turned to light.

The king seemed a bit taken aback at first; he was hardly used to people near him speaking so directly, without courtly circumlocutions. Especially women.

‘You are a blessed woman in more than one respect, my dear Sigrid,’ he said at last, taking her hand again. ‘Tomorrow when we have slept our fill in the royal palace after today’s feast, I shall summon Father Henri, and we will take care of this entire matter. Tomorrow, not now. It’s not proper for us to sit here together for very long, whispering.’

With the wave of a hand she had now given away her inheritance, Varnhem. No man could break his word to the king, nor any woman either, just as the king may never break his word. What she had done could not be undone.

But it was also practical, she realized when she had recovered a bit. The Holy Spirit could indeed be practical, and the ways of the Lord were not always inscrutable.

Varnhem and Arnäs lay a good two days’ ride from each other. Varnhem was outside Skara, not far from the bishop’s estate near Billingen Mountain. Arnäs was up in the north of the region, on the eastern shore of Lake Vänern, where the forest Sunnanskog ended and the woods of Tiveden began, near Kinnekulle Mountain. The Varnhem estate was newer and in much better condition, which is why she wanted to spend the coldest part of the year there, especially as the dreaded childbed approached. Magnus, her husband, wanted them to take his ancestral estate Arnäs as their abode, while she preferred Varnhem, and they had not been able to agree. At times they could not even discuss the subject in a friendly, patient manner as befitted a husband and wife.

Arnäs needed to be repaired and rebuilt. But it lay in the unclaimed borderlands along the edge of the forest; there was a great deal of common land and royal land that could be acquired by trade or purchase. Much could be improved, especially if she moved all her thralls and livestock from Varnhem.

This was not precisely the way the Holy Spirit had expressed the matter when He revealed Himself to her. She had seen a vision that was not altogether clear: a herd of beautiful horses shimmering in many colours like mother-of pearl. The horses had come running toward her in a meadow covered with flowers. Their manes were white and pure, their tails were raised haughtily, and they moved as playfully and lithely as cats. They were graceful in all their movements, not wild but not free either, since these horses belonged to her. And somewhere behind the gambolling, frisky, unsaddled horses came a young man riding on a silver stallion. It too had a white mane and raised tail. She knew the young man and yet did not. He carried a shield but wore no helmet. She didn’t recognize the coat of arms from any of her own kinsmen or her husband’s; the shield was completely white with a large blood-red cross, nothing more.

The young man reined in his horse right next to her and spoke to her. She heard all the words and understood them, and yet did not grasp their import. But she knew what they meant – she should give God the gift that was now needed most of all in the country where King Sverker ruled: a good place for the monks of Lurö to live. And Varnhem was a very good place.

When she came out onto the steps of the cathedral her head cleared with the cold, fresh air. She understood with sudden insight, almost as if the Holy Spirit was still upon her, how she would tell all this to her husband, who was coming toward her in the crowd carrying their cloaks over his arm. She regarded him with a cautious smile, utterly confident. She was fond of him because he was a gentle husband and a considerate father, although not a man to be respected or admired. It was hard to believe he was actually the grandson of a man who was his direct opposite, the powerful jarl Folke the Stout. Magnus was a slender man, and if he hadn’t been wearing foreign clothes he might be taken for anyone in the crowd.

When he came up to Sigrid he bowed and asked her to hold her own cloak while he first swung his large, sky-blue cloak lined with marten fur around him and fastened it under his chin with the silver clasp from Norway. Then he helped her with her cloak and tentatively caressed her brow with his soft hands, which were not the hands of a warrior. He asked her how she had managed to stand for such a long praise-song to the Lord in her blessed state. She replied that it hadn’t been any trouble, because she had brought Sot along to serve as support, and because the Holy Spirit had granted her a revelation. She spoke in the way she did when she wasn’t being serious. He smiled, thinking it was one of her usual jokes, and then looked around for his man who was bringing his sword from the church entryway.

When Magnus swept his sword in under his cloak and began fastening its scabbard, both his elbows jutted out, making him look broad and mighty in a way that she knew he was not. Then he offered Sigrid his arm and they made their way carefully through the crowd, where the most distinguished churchgoers now mixed with the common folk and thralls. In the middle of the marketplace Frankish acrobats were performing, along with a man who spit fire; pipes and fiddles were being played, and muffled drums could be heard over by one of the large ale tents. After a while Sigrid took a deep breath and bluntly told him everything at once.

‘Magnus, my dear husband, I hope you’ll take it with manly calm and dignity when you hear what I’ve just done,’ she began, taking another deep breath and continuing quickly before he could reply. ‘I have given my word to King Sverker that I will donate Varnhem to the Cistercian monks of Lurö. I can’t take back my word to a king, it’s irreversible. We’re going to meet him tomorrow at the royal estate to have the promise written out and sealed.’

As she expected, he stopped short to give her a searching glance, looking for the smile she always wore when she was teasing him in her own special way. But he soon realized that she was completely serious, and then anger overcame him with such force that he probably would have struck her for the first time if they hadn’t been standing in the midst of kinsmen and enemies and all the common folk.

‘Have you lost your wits, woman? If you hadn’t inherited Varnhem you’d still be withering away in the convent. It was only because of Varnhem that we were married at all.’

He managed to control himself and speak in a low voice, but with his teeth firmly clenched.

‘Yes, all that is true, my dear husband,’ she replied with her eyes lowered chastely. ‘If I hadn’t inherited Varnhem, your parents would have chosen another wife for you. I would have been a nun by now in that case. But Eskil and the new life I’m carrying under my heart would not have existed without Varnhem.’

Magnus did not reply. Just then Sot approached them with Eskil, who ran to his mother at once and took her hand, chattering excitedly about everything he had seen inside the cathedral.

Magnus lifted his son in his arms and stroked his hair lovingly as he regarded his lawful wife with something other than affection. But then he put the boy down and barked at Sot to take Eskil with her to watch the players; they would join her again soon. Sot took the boy by the hand and led him off whining and protesting.

‘But as you also know, my dear husband,’ Sigrid resumed quickly, ‘I wanted Varnhem to be my bridal morning gift, and I had that gift deeded to me under seal, along with little more than the cloak on my back and some gold for my adornment.’

‘Yes, that is also true,’ replied Magnus sullenly. ‘But even so, Varnhem is one-third of our common property, a third that you have now taken from Eskil. What I can’t understand is why you would do something like this, even though it is within your right.’

‘Let’s stroll over toward the players and not stand here looking as if we might be quarreling with each other, and I’ll explain everything.’ She offered him her arm.

Magnus looked around self-consciously, forced a smile, and took her by the arm.

‘All right,’ she said hesitantly. ‘Let’s begin with earthly matters, which seem to be filling your head the most right now. I will take all the livestock and thralls with me up to Arnäs, of course. Varnhem does have better buildings, but Arnäs is something we can rebuild from the ground up, especially now that we’ll have so many more hands to put to work. This way we’ll have a better place to live, particularly in the wintertime. More livestock means more barrels of salted meat and more hides that we can send to Lödöse by boat. You want so much to trade with Lödöse, and we can easily do so from Arnäs in both summer and winter, but it would be difficult from Varnhem.’

Leaning forward, he walked silently by her side, but she could see that he had calmed down and was starting to listen with interest. She knew that they wouldn’t have to argue now. She saw everything as clearly before her as if she had spent a long time planning it all out, although the whole idea was less than an hour old.

More leather hides and barrels of salted meat for Lödöse meant more silver, and more silver meant they could buy more seed. More seed meant that more thralls could earn their freedom by breaking new ground, borrowing seed, and paying them back twofold in rye that could be sent to Lödöse and exchanged for more silver. And then they could repair the fortifications to ensure Arnäs’ safety, especially in the frost of winter. By gathering all their forces at Arnäs instead of dividing their efforts between two places, they would soon grow richer and own even more land with all the newly broken ground. They would have a warmer, safer house, and leave a larger inheritance to Eskil than they could have otherwise.

When they had made their way to the front of the crowd, Magnus stood silent and pensive for a long time. Out of breath, Sot appeared with little Eskil in her arms; she held him up in front of her so that people could see from his clothing that she had the right to push through the crowd. Then the boy jumped down and stood in front of his mother, who gently laid her hands on his shoulders, stroked his cheek, and straightened his cap.

The players in front of them were busy building a high tower composed of nothing but people, with a little boy, perhaps only a couple of years older than Eskil, climbing alone to the very top. The people shouted in fear and amazement.

Eskil pointed eagerly and said he wanted to be a performer too, which made his father break out in surprisingly hearty laughter. Sigrid glanced at him cautiously and thought that with that laughter the danger had passed.

He noticed her sneaking a glance at him and kept laughing as he bent forward and kissed her on the cheek.

‘You are truly a remarkable woman, Sigrid,’ he whispered with no anger in his voice. ‘I’ve thought over what you said, and you’re right about everything. If we gather all our forces at Arnäs we will grow richer. How could any merchant have a better, more faithful wife than you?’

With downcast eyes she replied at once, softly, that no wife could ever have a kinder, more understanding husband than she did. But then she raised her glance, gazed at him gravely, and admitted that she’d had a vision in the church; all her ideas must have come from the Holy Spirit Himself, even the clever part that had to do with business.

Magnus looked a little cross, as if he didn’t really believe her, almost as if she were making fun of the Holy Spirit. He was much more devout than she was, and they both knew it. Her years in the convent had not softened her in the least.

When the players finished their performance they went off to the ale tent to collect their free ale and the well-turned piece of roast they had earned. Magnus picked up his son and walked with Sigrid at his side, with Sot ten respectful paces behind, and headed for the town gate; on the other side of the fence their wagons and retainers were waiting. On the way Sigrid told him about the vision that she’d had. She also offered her interpretation of the holy message.

It was well known that a difficult childbirth was often followed by another difficult one, and soon it would be time again. But by donating Varnhem she was ensured many prayers of intercession, and by men who were particularly knowledgeable about such prayers. She and the new child would be allowed to live.

More important, of course, was that their united lineages would now grow stronger as the power and wealth of the Arnäs estate increased. The only thing she was unsure of was who the young man might be on the silver horse with the thick white mane, its long white tail raised boldly in the air. Probably not the Holy Bridegroom, at any rate. He wouldn’t be likely to appear riding on a frisky stallion and carrying a shield on his arm.

Magnus was intrigued by the conundrum and pondered it a while; he began interrogating her about the size of the horses and the way they moved. Then he protested that such horses probably did not exist, and he wondered what she meant by saying that the shield had a cross of blood on it. In that case it would indeed be a red cross, but how could she know it was blood and not merely red paint?

She replied that she simply knew. The cross was red, and of blood. The shield was all white. She hadn’t seen much of the young man’s clothing because his shield concealed his breast, but he was wearing white garments. White, just like the Cistercians, but he was definitely no monk because he bore the shield of a warrior.

With interest Magnus asked about the shape and size of the shield, but when he found out it was heart-shaped and only big enough to protect the chest, he shook his head in disbelief and explained that he had never seen a shield like that. Shields were either big and round, like those once used when venturing out on Viking raids, or they were long and triangular so that warriors could move easily when gathered in a phalanx. A shield as small as the one she had seen in the vision would be more trouble than protection if anyone tried to use it in battle.

But no ordinary person could expect to understand everything in a revelation. And in the evening they would pray together, grateful that the Mother of God had showed them her kindness and wisdom.

Sigrid sighed, feeling great relief and serenity. Now the worst was over, and all that was left was to cajole the old king so that he wouldn’t pass off her gift as his own. Since the king had grown old, people had begun to worry about the number of daily prayers of intercession offered on his behalf; he had already founded two cloisters to ensure this would be done for him. Everyone knew about this, his friends as well as his enemies.

King Sverker had a ferocious hangover and was in a rage when Sigrid and Magnus entered the great hall of the royal palace. The king now had to settle a good day’s worth of decisions about everything, from how the thieves caught at the market the day before were to be executed – whether they should just be hanged or tortured first – to questions regarding disputes about land and inheritance that could not be resolved at a regular ting; the assembly of noblemen.

What made him more cross than the hangover was the day’s news about his next youngest son, the scoundrel, who had deceived him in a deplorable way. His son Johan had left on a plundering raid to the province of Halland in Denmark; that in itself was probably not so dangerous. Young men were liable to do such things if they wanted to gamble with their lives instead of just playing at dice. But Johan had lied about the two women he had abducted and brought home to thralldom, claiming they were foreign women he had kidnapped at random. But now a letter had arrived from the Danish king, unfortunately claiming something quite different, which no one doubted. The two women were the wife of the Danish king’s jarl in Halland and her sister. It was an affront and an outrage, and anyone who was not the son of a king would have been executed at once for such a crime. The king had reprimanded him, of course. But it wasn’t enough to send back the women as blithely as they had been stolen. It was going to cost a great deal of silver, no matter what; in the worst case they might have a war on their hands.

King Sverker and his closest advisers had become embroiled in such a quarrel that everyone in the hall was soon aware of the whole story. The only thing that was certain was that the women had to be returned. But agreement ended there. Some thought it would be a sign of weakness to make payments in silver; it might give the Danish king, Sven Grate, the incentive to invade, plunder, and seize land. Others thought that even a great deal of silver would be less costly than being invaded and plundered, no matter who the victor might be in such a war.

After a long, exhaustive argument the king suddenly gave a weary sigh and turned to Father Henri de Clairvaux, who sat waiting at the far end of the hall for the Lurö case to be presented.

The priest’s head was bowed as if in prayer, with his white cowl drawn over his face so no one could see whether he was praying or sleeping, although the latter was more likely. In any case, Father Henri hadn’t been able to follow the heated discussion, and when he replied to the king’s summons it sounded like Latin. As there was no other clergyman present, no one understood. The king looked angrily around the hall; red in the face, he roared, ‘Bring me some devil who can understand this snooty cleric language!’

Sigrid instantly saw her opportunity. She stood up and walked forward in the hall with her head bowed, curtseying deferentially first to King Sverker and then to Father Henri.

‘My king, I am at your service,’ she said and stood waiting for his decision.

‘If there is no man here who speaks that language, then so be it,’ the king sighed wearily again. ‘By the way, how is it that you speak it, Sigrid, my dear?’ he added more kindly.

‘I’m afraid I must admit that the only thing I really learned during my banishment to the cloister was Latin,’ replied Sigrid demurely. Magnus was the only man in the hall who noticed her mocking smile; she often spoke in this manner, saying one thing but meaning another.

The king promptly asked Sigrid to sit down next to Father Henri, explain the situation to him, and then ask for his view of the matter. She obeyed at once, and while she and Father Henri began a hushed conversation in the language which they alone understood among all the people in the hall, a mood of embarrassment began to spread. The men looked querulously at one another, some shrugged their shoulders, some demonstratively folded their hands and raised their eyes to heaven. A woman in the king’s court among all these good men? But so be it. What was already done could not be undone.

After a while Sigrid stood up. To quiet the muttering in the hall, she explained in a loud voice that Father Henri had considered the matter and now believed that the wisest thing to do would be to force the blackguard to marry the sister of the jarl’s wife. But the jarl’s wife must be sent home with gifts and fine clothing, with banners and fanfare. King Sverker and his scoundrel son would thus have to refuse a dowry, so the question of silver was solved. No consideration could be given to what the knave himself thought; if he and the sister of the jarl’s wife could be married, the blood bond would prevent a war. But the rascal would have to do something to pay for his roguish behavior. War would still be the most costly solution.

When Sigrid fell silent and sat down, it was quiet at first while those assembled considered the implications of the monk’s proposal. But gradually a murmur of approval spread. Someone unsheathed his sword and slammed the broadside hard on the heavy tabletop that ran along both sides of the hall. Others followed his example and soon the hall was booming with the clamour of weapons. And so the matter was decided for the time being.

King Sverker now decided to deal with the question of Varnhem at once. He waved over a scribe, who began to read aloud the document the king had ordered drawn up to confirm the matter before the law. According to the text, however, it sounded as if the gift came from the king alone.

Sigrid asked to see the document so that she could translate it for Father Henri, but she also suggested cautiously that perhaps Herr Magnus should take part in the ensuing discussion. ‘Certainly, certainly,’ said the king with a wave of dismissal, and he gestured to Magnus to step forward in the hall and take a seat next to his wife.

Sigrid quickly translated the document for Father Henri, who leaned his head back and tried to follow along in the text as Sigrid pointed. When she was ready she added hastily, so it looked as if she were still translating, that the gift was from her and not from the king, but that according to the law she needed the king’s approval. Father Henri gave her a brief glance and a smile resembling her own, then nodded pensively.

‘Well,’ said the king impatiently, as if he wanted to dispose of the matter quickly, ‘does the Reverend Father Henri have anything to say or suggest in this matter?’

Sigrid translated the question, looking the monk straight in the eye, and he had no trouble understanding her intentions.

‘Hmm,’ he began cautiously, ‘it is a blessed deed to give to the most assiduous workers in His garden. But before God as before the law, a gift may be accepted only when one is quite certain who is the donor and who is the recipient. Is this His Majesty’s own property which we will now so generously share?’

He waved his hand in a little circle as a sign to Sigrid to translate. She reeled off the translation in a monotone.

The king was clearly embarrassed and gave Father Henri a dark look, while Father Henri gazed at the king in a friendly manner, as if he assumed everything was in order. Sigrid said not a word, waiting.

‘Yes, perhaps… perhaps,’ muttered the king self-consciously. ‘One might say that for the sake of the law the gift must come from the king, so that no one will be able to complain about the matter. But the gift also comes from Fru Sigrid who is here among us.’

While the king hesitated, Sigrid translated what he had just said, in the same formal, monotonous voice as before. Father Henri’s face brightened as if in friendly surprise when he now heard what he already knew. Then he shook his head slowly with a smile and explained, in quite simple words but with all the serpentine courtliness required when admonishing a king, that before God it would probably be more suitable to cleave to the whole truth even in formal documents. So if this letter were now drawn up again with the name of the actual donor, and with His Majesty’s approval and confirmation of the gift, then the matter would be settled and prayers of intercession could be duly vouchsafed to His Majesty as well as to the donor herself.

And so the matter was decided in just this way, precisely as Sigrid had wished. Nothing else was possible for King Sverker; he quickly made the decision, adding that the letter should be drafted in both the vernacular and Latin; he would affix his seal to it that very day. And perhaps now they could cheer themselves up a bit by returning to the question of how and when the executions were to take place.

In Father Henri and Fru Sigrid, two souls had found each other. Or two human beings on earth with quite similar outlooks and intelligence.

The question of Varnhem was thus decided, at least for now.

Around the Feast of Filippus and Jakob, the day when the grass should be green and lush enough to let out the livestock to graze and when the fences had to be inspected, Sigrid was gripped by fright as if a cold hand had seized her heart.

She felt that her time had come. But the pain vanished so quickly that it must have been her imagination.

She had been walking with little Eskil, holding his hand, heading down to the stream where the monks and their lay brothers were busy raising a huge mill-wheel into position, using block and tackle and many draft animals.

Sigrid had spent a great deal of time at the building sites. Father Henri had patiently walked her through all of the plans. And she had taken two of her best thralls with her, Svarte, who was Sot’s fecundator, and Gur, who had left his wife and brood up in Arnäs. Sigrid carefully translated into their language what Father Henri had described.

Magnus had complained that she still didn’t have any employment for the best thralls, at least not the male ones, down at Varnhem. They should have been busy on the construction work up at Arnäs. But Sigrid had stood firm, explaining that there were many useful things to be learned from the Burgundian lay brothers and the English stonemasons Father Henri had engaged. As so often before, she had pushed her will through, although it was difficult to explain to a man from Western Götaland that the foreigners were much better builders than local workers.

In only a few months Varnhem had been transformed into a huge construction site, with the echo of hammer blows, the noise of saws, and the creaking and rattling of the big sandstone grinding wheels. There was life and movement everywhere. At first glance it might look frenzied and chaotic, like looking down into an anthill in the spring, when the ants seem to be running amok. But there were precise plans behind everything that was being done. The steward was an enormous monk named Guilbert de Beaune. He was the only monk who joined in the work himself; otherwise the brown- robed lay brothers took care of all the manual labor. It might be said that Brother Lucien de Clairvaux also broke this rule. He was the cloister’s head gardener, and he refused to entrust the sensitive planting to anyone else. It was a bit late in the year to be planting and difficult to do it successfully without the right touch or the right eye for the task.

The other monks, who had taken over the longhouse for the time being as both residence and chapel, busied themselves primarily with spiritual matters or with writing.

After some time Sigrid had volunteered both Svarte and Gur to help the lay brothers; her thought was that the two should initially become apprentices rather than offer any particular help. Some of the lay brothers had come to Father Henri and complained that the boorish and untrained thralls were too clumsy at their tasks. But Father Henri waved aside such complaints because he understood full well Sigrid’s intentions for these apprentices. In fact, he had spoken in private with Brother Guilbert about the matter. To the vexation of many lay brothers, just as Svarte and Gur began to learn enough to be helpful at one work site, they would be sent on to the next, where the fumbling and foolish incompetence would begin anew. Cutting and polishing stone, shaping red-hot iron, fashioning waterwheels from oak pieces, lining a well or canal with stone, weeding garden plots, chopping down oak and beech trees and shaping the logs for various purposes: soon the two burly thralls had learned the basics of most tasks. Sigrid queried them about their progress and made plans for how they might be used in the future. She envisioned that they would both be able to work their way to freedom; only someone who knew how to do something of value could support himself as a freedman. Their faith and salvation interested her less, in fact. She had not coerced any of her thralls except Sot to be baptized, and that was only because of her special need for support on the church floor when the cathedral was being consecrated.

It had been a peaceful time. As mistress of a household Sigrid hadn’t had as much to do as she would have had as Varnhem’s owner, or if she had to be responsible for all the farm work up at Arnäs. She tried to think as little as possible about the inevitable, what would come to her as surely as death came to everyone, thralls and people alike. Since the longhouse was not consecrated as a cloister, she could participate whenever she liked in any of the five daily prayers held by the monks. The more time passed, the more assiduously she had taken part in the prayer hours. She always prayed for the same things: her life and that of her child, and that she might receive strength and courage from the Holy Virgin and be spared the pain she had endured the last time.

Now she walked with cold sweat on her brow, softly and gingerly as if she might call forth the pain with movements that were too strenuous. She was headed away from the construction noise, up toward the manor. She called Sot over to her and did not have to tell her what was wrong. Sot nodded, grunting in her laconic language, and hurried off toward the cookhouse where she and the other thrall women began preparing for dinner. They quickly carried out everything that had to do with baking bread and cooking meat, swept and mopped the floor clean, and then brought in straw beds and fur rugs from the little house where Sigrid stored all her own supplies. When all was ready and Sigrid was about to lie down inside, she felt a second wave of pain, which was so much worse than the first that she went white in the face and collapsed. She had to be led to the bed in the middle of the floor. The thrall women had blown more life into the flames, and in great haste they cleaned tripod kettles, which they filled with water and set over the fire.

When the pain subsided, Sigrid asked Sot to fetch Father Henri and then see to it that Eskil was kept with the other children a good distance away, so that he would not have to hear his mother’s screams, if it should come to that. But someone would also have to watch the children so they wouldn’t come too close to the perilous mill-wheel, which more than anything else seemed to arouse their curiosity. The children should not be left unattended.

She lay alone for a while and looked out through the smoke vent in the roof and the large open window in one wall. Outside the birds were singing – the finches that sang in the daytime before the thrushes took over and made all the other birds fall silent in shame.

Her brow was sweating, but she was shivering with cold. One of her thrall women shyly approached and stroked her forehead with a moist linen cloth but didn’t dare look her in the eye.

Magnus had admonished her to send for good women from Skara when her time was nearing, and not to give birth among thrall women. But he was just a man, after all. He wouldn’t understand that the thrall women, who were accustomed to breeding more often than others, had a good knowledge of what needed to be done. They didn’t have white skin, elegant speech, or courtly manners, like the women Magnus would have preferred, who would have filled the room with their chatter and flighty bustling. The thrall women were knowledgeable enough to suffice, if indeed mortal help alone would be enough. The Holy Virgin Mary would either help or not help, regardless of the souls that were in the room.

The thrall women did have souls like other people; Father Henri had told her as much in strong and convincing terms. And in the Kingdom of Heaven there were no freedmen or slaves, wealthy or low-born, only the souls who had proved themselves worthy through acts of goodness. Sigrid thought that this might well be true.

When Father Henri came into the room she saw that he had his prayer vestments with him. He had understood what kind of help she now sought. But at first he didn’t let on, nor did he bother to chase out the thrall women who were rushing around sweeping, or who came running in with fresh buckets of water, and linen and swaddling clothes.

‘Greetings, honorable Mistress Sigrid, I understand that now we are nearing an hour of joy here at Varnhem,’ said Father Henri, his expression calmer and more kindly than his voice.

‘Or an hour of woe, Father, we won’t know until it’s over,’ whimpered Sigrid, staring at him with eyes full of terror as she felt more pain on its way. But she was just imagining it; none came.

Father Henri pulled over a little three-legged stool to her bedside and reached out a hand to her. He held her hand and stroked it.

‘You’re a clever woman,’ he said, ‘the only one I’ve met in this temporal world who has the wit to speak Latin, and you also understand many other things, like teaching the thralls what we know how to do. So tell me, why should what awaits you be so unusual, when all other women go through it? High-born women like yourself, thralls and wretched women, thousands upon thousands of others. Just think, at this very moment you are not alone on this earth. As we speak, at this moment, you are together with ten thousand women the world over. So tell me, why should you have anything to fear, more than all the others?’

He had spoken well, using a sermon-like tone, and Sigrid thought he had probably been thinking about this for days – the first words he would say to her when the hour of dread approached. She couldn’t help smiling when she looked at him, and he saw by her smile that she had seen through him.

‘You speak well, Father Henri,’ she said in a weak voice. ‘But of those ten thousand women you speak of, almost half will be dead tomorrow, and I could be one of them.’

‘Then I would have a hard time understanding Our Saviour,’ said Father Henri calmly, still smiling with his eyes, which remained fixed on hers.

‘There is something Our Saviour does that you still don’t understand, Father?’ she whispered as she braced herself in anticipation of the next contraction.

‘That’s true, of course,’ nodded Father Henri. ‘There are even things that our founder, Holy Saint Bernard de Clairvaux, doesn’t understand. Such as the terrible defeats our knights are now suffering in the Holy Land. He wants more than anyone for us to send more men; he wants nothing more than victory for our righteous cause against the infidels. And yet we were beaten badly, despite our strong faith, despite our good cause, despite the fact that we are fighting against evil. So of course it’s true that we human beings cannot always understand Our Saviour.’

‘I want to have time to confess,’ she whispered.

Father Henri chased out the thrall women, pulled on his prayer vestments, and blessed her. Then he was ready to hear her confession.

‘Father forgive me, for I have sinned,’ she gasped with fear shining in her eyes. She had to take a few deep breaths and collect herself before continuing.

‘I’ve had ungodly thoughts, worldly thoughts. I gave Varnhem to you and yours not only because the Holy Spirit told me that it was a right and just cause. I also hoped that with this gift I would be able to appease the Mother of God because in foolishness and selfishness I had asked her to spare me from more childbeds, even though I know it’s our duty to populate the earth.’

She had been talking low and fast, waiting for the next jab of pain, which struck just as she finished speaking. Her face contorted and she bit her lip to keep from screaming.

Father Henri got up and fetched a linen cloth, dipping it in cold water in a pail by the door. He went to her, raised her head, and began bathing her face and brow.

‘It is true, my child,’ he whispered, leaning forward to her cheek and feeling her fiery fear, ‘that God’s grace cannot be bought for money, that it’s a great sin both to sell and buy what only God can bestow. It’s also true that you in your mortal weakness have felt fear and have asked the Mother of God for aid and consolation. But that is no sin. And as far as the gift of Varnhem is concerned, it was prompted by the Holy Spirit descending upon you and giving you a vision which you were ready to accept. Nothing in your will can be stronger than His will, which you have obeyed. I forgive you in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. You are now without sin and I will leave you so, for I must go and pray.’

He carefully laid her head back down and could see that somewhere deep inside her pain she seemed relieved. Then he left quickly and brusquely ordered the women back into the house; they rushed in like a flock of black birds.

But Sot stayed where she was and tugged cautiously on his robe, saying something that he didn’t understand at first, since neither of them was fluent in the common Swedish speech. She renewed her effort, speaking very slowly, and supplementing her words with gestures. It then dawned on him that she had a secret potion made of forbidden herbs that could alleviate pain; the thralls used to give it to their own who were about to be whipped, maimed, or gelded.

He looked down at the diminutive woman’s dark face as he pondered. He knew quite well that she was baptized, so he must talk to her as if she were one of his flock. He also knew that what she told him might be true: Lucien de Clairvaux, who took care of all the garden cultivation, had many recipes that could achieve the same effect. But there was a risk that the potion the thrall women spoke of had been created using sorcery and evil powers.

‘Listen to me, woman,’ he said slowly and as clearly as he could. ‘I’m going to ask a man who knows. If I come back, then give drink. No come back, no give drink. Swear before God to obey me!’

Sot swore obediently before her new God, and Father Henri hurried off to converse with Brother Lucien first, before he gathered all the brothers to pray for their benefactress.

A short time later he spoke to Brother Lucien, who vehemently rejected the idea in fright. Such potions were very strong; they could be used for those who were wounded, dying, or for medicinal purposes when an arm or foot had to be amputated. But on pain of death one must not give such a potion to a woman giving birth, for then one would be giving it to the child as well, who might be born forever lame or confused. As soon as the child was born, of course, it would be permitted. Although by that time it was usually no longer necessary. But it could be interesting to hear what that pain-killing potion was composed of; perhaps one might gain some new ideas.

Father Henri nodded shamefully. He should have known all this, even though he specialized in writing, theology, and music, not medicine or horticulture. He hurriedly gathered the brothers to begin a very long hour of prayer.

For the time being, Sot had decided to obey the monk, even though she thought it was a shame not to lighten her mistress’s suffering. She now took charge of the other women in the room, and they pulled Sigrid out of bed, let down her hair so it flowed free: long, shiny, and almost as black as Sot’s own hair. They washed her as she shivered with cold, and then pulled a new linen shift over her head and made her walk about the room, to hasten the birth.

Through a fog of fear, Sigrid staggered around the floor between two of her thrall women. She felt ashamed, like a cow being led about at market. She heard the bell chime from the longhouse but was unsure if it was only her imagination.

The next wave of pain hit; it started deeper inside her body, and she could feel that it would last longer this time. Then she screamed, more from terror than pain, and sank down on the bed. One of the thrall women held Sigrid under the arms from behind and lifted her body upwards, while they all shrieked at once that she had to help, she had to push. But she didn’t dare push. She must have fainted.

When the twilight turned to night and the thrushes fell silent, a stillness seemed to come over Sigrid. The pains that had come so often in the last few hours seemed to have stopped.

Sot and all the others knew this was an ominous sign. Something had to be done. Sot took one of the others with her and they padded out into the night, sneaking past the longhouse where the murmuring and singing of the monks could be heard faintly through the thick walls, and on to the barn. They brought out a young ram with a leather rope around its neck and led it away in the falling darkness toward the forbidden grove. There they bound the rope around one rear hoof and slung the other end over one of the huge oak branches in the grove. As Sot pulled on the rope so that the ram hung with one hind leg in the air, the other thrall woman fell upon the animal. She grabbed it around the shoulders, and forced the animal toward the ground with all her weight, as she drew out a knife and slit its throat. They both hoisted up the struggling, screeching ram, as blood sprayed in all directions. After they tied the rope to a root of the tree, they stripped off their shifts and stood naked beneath the shower of blood and smeared it into their hair, over their breasts, and between their legs as they prayed to Frey.

When the morning dawned, Sigrid awoke from her torpor with the fires of hell burning in her anew, and she prayed desperately to the dear blessed Virgin Mary to save her from the pain, to take her now, if that was how it was to end, but at least to spare her from the pain.

The thrall women, who had been dozing around her, came quickly to life and started running their hands over her body and speaking rapidly to one another in their own unintelligible tongue. Then they began to laugh, smiling and nodding eagerly to her and to Sot, whose hair was so soaked that it hung straight down, dripping cold water as she bent over Sigrid, telling her that now was the time, now her son would soon come, but for the last time she must try to help. And the women took her under the arms and raised her halfway up in a sitting position, and Sigrid screamed wild prayers until she realized she might wake her little Eskil and frighten him. So she bit her wounded lip again and it began to bleed anew, and her mouth was filled with the taste of blood. But softly, in the midst of all that was unbearable, she found more and more hope, as if the Mother of God were now actually standing at her side, speaking gently to her and encouraging her to do as her clever and loyal thralls instructed. And Sigrid bore down and bit her lip again to keep from screaming. Now the monks’ voices could be heard out in the dawn, very loud, like a praise-song or a psalm meant to drown out the terror.

Suddenly it was over. She saw through her sweat and tears a bloody bundle down below. The women in the room bustled about with water and linen cloths. She sensed them washing and chattering, she heard some slaps and a cry, a tiny, tremulous, bright sound that could only be one thing.

‘It’s a fine healthy boy,’ said Sot, beaming with joy. ‘Mistress has borne a well-formed boy with all the fingers and toes he should have. And he was born with a caul!’

They lay him, washed and swaddled, next to her aching, distended breasts, and she gazed into his tiny wrinkled face and was amazed he was so small. She touched him gently and he got an arm free and waved it in the air until she stuck out a finger, which he instantly grabbed and held tight.

‘What will the boy be named?’ asked Sot with a flushed, excited face.

‘He shall be called Arn, after Arnäs,’ whispered Sigrid, exhausted. ‘Arnäs and not Varnhem will be his home, but he will be baptized here by Father Henri when the time comes.’

Получить полную версию книги можно по ссылке - Здесь

| Следующая страница |

|